BOARD

2018.11.06 12:12:12

| 전시서문

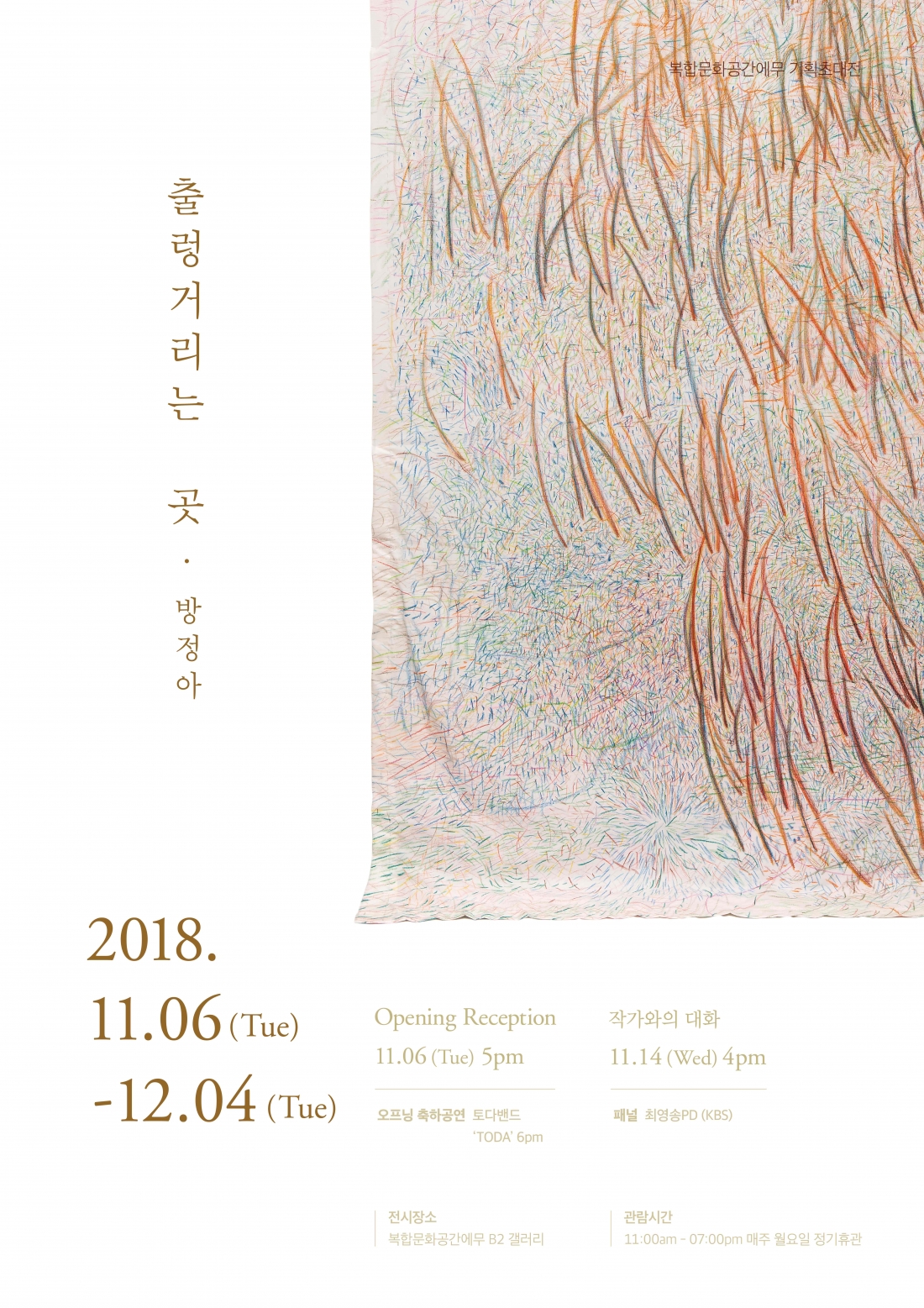

출렁거리는 곳

2018년은 지구상에서 마지막 남은 냉전유산을 걷어치우는 기념비적인 세계평화의 해다. 남북미 정상이 한반도 비핵화와 평화체제 구축을 위해 합의하였고, 그 과정이 진행되고 있다. 이 급변상황을 예상조차 할 수 없던 작년 하반기에 핵전쟁 공포를 신체상으로 표현하는 회화 작업을 방정아 작가에게 요청했고, 그는 1년여 만에 작품 20점을 완성하여 여기에 전시하게되었다. 출품작은 모두 신작으로써 분단통증의 (고고학적) 현 층위를 리얼하게 보여주면서, 동시에 신체의 사라져감과 새 생명에로의 교체 예감까지 표현하고 있다. 교차되는 시대가 반영된 ‘생성의 전시’다.

Where It Heaves And Churns

The year 2018 saw a monumental change; the beginning of a new era of world peace with the last remnants of the cold war finally receding into history. An agreement on the denuclearisation of the Korean Peninsula and the establishment of peace in the region has been reached by the two Korean leaders and the US president, and the process is underway. Late last year, when this sudden change in the political landscape was unimaginable, we asked Bang Jeong-Ah to produce works depicting the fear of nuclear war, expressed in the form of bodily pain. Within a year, she has completed twenty new works that we are eager to share with the public. Bang Jeong-Ah’s new works, to be shown for the first time at this exhibition, vividly express a new (archaeological) layer of pain in the divided nation and through the morphing and blurring bodies they appear to invite new life to take hold. This ‘exhibition of naissance’ echoes a new era at a crossroa ds.

| 작가비평

나는 태평양이 내려다보이는 언덕 위의 노란 집을 찾아 부산으로 갔다. 방정아 작가가 작업 하는 그곳의 작고 허름한 집은 피난민 판잣집을 저층으로 한 고고학적인 현재 층 같았다. 베란다 아래로 펼쳐진 바다는 난잡한 전깃줄에 가려서 상처를 더 드러냈고, 반면 떠 있는 크고 작은 배들은 기억상실증에 걸린 듯 태연했다. 그는 비좁은 작품 보관실에서 빽빽이 들어차 있는 그림들을 보여주었다. 미리 도록에서 살펴보긴 했지만, 실물은 그게 아니었다. 그냥 이곳이었다. (작가와 함께 작업실을 나가서 곧 마주치게 될 사람들만 보면 그의 작품은 완성되는 것이었다. 내리막 굽잇길에서 거리에서 자갈치시장에서 전철에서…….) 그래서 작품들을 보고 거위처럼 큰 소리로 놀라움을 표했고, 내예견력을 스스로 치하했다. 확실히 그는 ‘신체’와 ‘통증’의 작가였다. 2017년, 작년 한해는 북핵이 연일 뉴스를 장식하면서 3차 대전 공포가 한반도 상공을 떠돌고 있었다. 전쟁 반대 목소리 대신 사드 배치와 전쟁 불사 논리가 광기 어리게 여론을 주도했다. 적어도 예술가가 이런 대량학살전쟁(인류종말전쟁)에 반대하는 작품을 만들지 않으면 그게 도대체 뭔가? 라는 생각이었다.

방정아 작가를 떠올렸다. 책꽂이에서 도록을 꺼내 보았다. 역시. 그는 신체를 그리는 작가였다. 또 하나, 그 신체에는 자신의 작업실 현장처럼 고고학적 층위가 들어 있었다. 그를 초대하는 전시를 열기로 아직은 혼자서 결정한 상태였다. 전화를 걸었다. 북핵, 전쟁 위험 이런 사태를 신체의 통증으로 표현해 주시오, 하고 요청했다. 그게 위기가 최고조에 이른 작년 11월이었다. 그러니까 딱 1년 전이다. 그는 처음 제안을 받고서 난감해 했지만 수용했다. 작업을 하기로 한 직접적인 이유는 아마도 그에게 들려준, 천안함과 연평도 사건 때 군대에서 투입 대기 중이었던 내 아들 이야기였던 것 같다. 그때 난 방작가의 반응을 보면서 이 인간은 참 구체성을 그리는 작가란 생각을 했다. 벌써 작년 일이다.

두 번째 그 노란 집 작업실을 방문했을 때 작업 중인 그림들이 상당수였다. 나는 적이 안심이 됐다. 게다가 그가 본인이 앓은 통증 목록을 보여줄 때 난 박수를 쳤다. 이석증, 늑간 신경염은 이번 작품 제목에 들어있다. 그 외도 족히 열 가지는 넘었다. 난 재차 작가의 구체성을 확인하면서 놀랐다. 아, 이 작가의 이런 구체성이 ‘신체의 고고학’을 만들어내는구나! 폐허가 된 유적의 층위를 내장하고 있는 고고학적 층위에는 당시 인간들의 영광과 실패, 희로애락이 고스란히 담겨 있다. 하지만 보여 지는 것은 무심한 유적일 뿐이다. 난 그 무심함이 표현돼야 한다고 여긴다. 보여지는 것을 보여줘야 한다는 철학이다. 그 속에 무엇을 담든 다음 문제다. 100미터 아래 지하수를 찾으려면 땅거죽을 조사해서 알 수 있을 뿐이다. 바로 이런 것이 ‘신체 고고학’적 미술작업이 아닐까 한다.

이제 작가의 결과물이 전시된다. 출품작 스무 점은 모조리 신작이다. 이번 작품들은 그러나 ‘신체 고고학’ 이상의 진전이 뚜렷이 보인다. 예전 작품에 비해 신체의 선과 점이 진동하고 있기 때문이다. 이런, 방정아 작가가 무당이 되었나? <출렁거리는 땅>은 대표적이다. <물린 얼굴>은 어떤가? 이 물린 얼굴은 ‘무엇’의 표상인데, 그 ‘무엇’이 이를 테면 ‘상처 속에 우주가 있다’는 텍스트의 함의에 존재한다면, 이것을 제대로 표현하기 위해선 무당이 작두를 타지 않고서야 될 법한 일일까?

더 나아가서 이번 신체들은 형태까지도 사라져 가고 있다. 마치 그 자리를 새로운 생명이 밀물처럼 들어올 것 같은 예감이다. 단언컨대 모든 작품이 그렇다. 수사가 아니다. 교차되는 시대가 반영된 ‘생성의 전시’다.

김영종 (관장)

I traveled to Busan to visit a yellow house on a hill looking over the Pacific Ocean. The small rundown house where Bang Jeong-Ah creates her works appeared as if it were a new archaeological layer on top of the layers accumulated since refugee shacks were built there during the Korean War. The ocean view from the balcony, scarred with crisscrossing electric cables, reminded me of the traumas the war had left behind; while fishing boats, both big and small, floating on the ocean seemed to have forgotten

or be oblivious to the past. Bang showed me her works crammed into a small storage space. I had seen her works before in printed catalogues, but they didn’t come close to the real thing. Bang’s works wholly reflected where she lives. (After leaving the studio with Bang, I would see the people who were the subject of her art everywhere. Down the crooked alley, at the Jagalchi Fish Market, on the subway….) I shrieked like a goose, pleased that my expectations had been justified. Indeed, Bang was an artist who captured perfectly ‘body’ and ‘pain’. Throughout 2017, North Korean nuclear tests were a permanent feature on the news. The fear of World War III breaking out was palpable among the people of the Korean peninsula. The antiwar voices were drowned out by the clamour for THAAD deployment and warmongering hysteria that dominated public opinion. What could artists do, other than to provide an alternative to this potentially genocidal aggression (which, in all likelihood, will lead us to the end of civilisation), I wondered…?

Bang Jeong-Ah immediately sprang to my mind. From my bookshelf, I pulled out a catalogue featuring her works. As I remembered, she was an artist who drew bodies. Better still, her bodies had an archaeological dimension to them, just like her studio. I decided to invite her to hold an exhibition. I gave her a call and asked if she could produce works on the North Korea crisis and the threat of war, expressed in the form of bodily pain. It was early November 2017, exactly a year ago.

At first Bang was reluctant, but eventually agreed. I told her about the story of my son, who had been doing his military service during the ROKS Cheonan sinking and the Bombardment of Yeonpyeong, and as a result waiting for a possible and imminent deployment. I suspect that the story of his predicament changed her mind. Observing her reaction, I couldn’t help thinking that she was the kind of artist who would encapsulate the tangible reality of human lives.

The second time I visited her yellow house studio, Bang was already working on several pieces. I was relieved. When she showed me the list of maladies she suffered over the years, I was excited by its potential. Amongst a dozen of them, Otolithiasis and intercostal neuritis were the titles of paintings that she was working on. I marveled at her ability once again to capture tangible pain in her art. That was what gave life to her ‘archaeology of bodies’. The layers of archaeological sites contain the glory, failure and the joys and sorrows of life from bygone eras. Yet what is left to be seen is the ruins, indifferent to human affairs. I believe art should reflect that indifference. My philosophy is that art should be about showing what is left to be seen. What meanings one might add comes later. To find water running 100 meters below the ground, you must examine the surface. To me, that is what creating the ‘archaeology of bodies’ is all about.

Now, Bang Jeong-Ah’s works are about to go on display. Twenty new works have been created which have never been shown before. But these new works go a step further than the previous ‘archaeology of bodies’, because the lines and dots of her new bodies have life and vibrate. My God, has Bang Jeong-Ah turned into a shaman?suggests so, and what about ? That bitten face represents something, and if that ‘something’ is, say, a visual apothegm of ‘a scar can reveal a universe’, then she must be a kind of shaman connected directly to the spirits to allow her to express that idea with such finesse. In her new works, bodies are morphing and allowing new life to flood in. It is conspicuous in all of her new works. This is not mere rhetoric, this ‘exhibition of naissance’ echoes a new era at a crossroads.

or be oblivious to the past. Bang showed me her works crammed into a small storage space. I had seen her works before in printed catalogues, but they didn’t come close to the real thing. Bang’s works wholly reflected where she lives. (After leaving the studio with Bang, I would see the people who were the subject of her art everywhere. Down the crooked alley, at the Jagalchi Fish Market, on the subway….) I shrieked like a goose, pleased that my expectations had been justified. Indeed, Bang was an artist who captured perfectly ‘body’ and ‘pain’. Throughout 2017, North Korean nuclear tests were a permanent feature on the news. The fear of World War III breaking out was palpable among the people of the Korean peninsula. The antiwar voices were drowned out by the clamour for THAAD deployment and warmongering hysteria that dominated public opinion. What could artists do, other than to provide an alternative to this potentially genocidal aggression (which, in all likelihood, will lead us to the end of civilisation), I wondered…?

Bang Jeong-Ah immediately sprang to my mind. From my bookshelf, I pulled out a catalogue featuring her works. As I remembered, she was an artist who drew bodies. Better still, her bodies had an archaeological dimension to them, just like her studio. I decided to invite her to hold an exhibition. I gave her a call and asked if she could produce works on the North Korea crisis and the threat of war, expressed in the form of bodily pain. It was early November 2017, exactly a year ago.

At first Bang was reluctant, but eventually agreed. I told her about the story of my son, who had been doing his military service during the ROKS Cheonan sinking and the Bombardment of Yeonpyeong, and as a result waiting for a possible and imminent deployment. I suspect that the story of his predicament changed her mind. Observing her reaction, I couldn’t help thinking that she was the kind of artist who would encapsulate the tangible reality of human lives.

The second time I visited her yellow house studio, Bang was already working on several pieces. I was relieved. When she showed me the list of maladies she suffered over the years, I was excited by its potential. Amongst a dozen of them, Otolithiasis and intercostal neuritis were the titles of paintings that she was working on. I marveled at her ability once again to capture tangible pain in her art. That was what gave life to her ‘archaeology of bodies’. The layers of archaeological sites contain the glory, failure and the joys and sorrows of life from bygone eras. Yet what is left to be seen is the ruins, indifferent to human affairs. I believe art should reflect that indifference. My philosophy is that art should be about showing what is left to be seen. What meanings one might add comes later. To find water running 100 meters below the ground, you must examine the surface. To me, that is what creating the ‘archaeology of bodies’ is all about.

Now, Bang Jeong-Ah’s works are about to go on display. Twenty new works have been created which have never been shown before. But these new works go a step further than the previous ‘archaeology of bodies’, because the lines and dots of her new bodies have life and vibrate. My God, has Bang Jeong-Ah turned into a shaman?

KIM YeongJong (Director)

| 전시정보

전 시 기 간 2018년 11월 6일(화) - 12월 4일(화) * 매주 월요일 정기휴관

관 람 시 간 오전 11시 - 오후 7시

전 시 장 소 복합문화공간에무 B2 갤러리

오프닝리셉션 2018년 11월 6일(화) 5pm *오프닝 축하공연 토다밴드 TODA 6PM (본사 B1 팡타개라지)

작가와의대화 2018년 11월 14일(수) 4pm *패널 최영송 PD (KBS)